Multiple Exceptions (user mode) - Modeling Example

Multiple Exceptions (user mode) - Modeling Example Multiple Exceptions (kernel mode)

Multiple Exceptions (kernel mode) Multiple Exceptions (managed space)

Multiple Exceptions (managed space)- Multiple Exceptions (stowed)

Dynamic Memory Corruption (process heap)

Dynamic Memory Corruption (process heap) Dynamic Memory Corruption (kernel pool)

Dynamic Memory Corruption (kernel pool)- Dynamic Memory Corruption (managed heap)

False Positive Dump

False Positive Dump Lateral Damage (general)

Lateral Damage (general)- Lateral Damage (CPU mode)

Optimized Code (function parameter reuse)

Optimized Code (function parameter reuse) Invalid Pointer (general)

Invalid Pointer (general)- Invalid Pointer (objects)

NULL Pointer (code)

NULL Pointer (code) NULL Pointer (data)

NULL Pointer (data) Inconsistent Dump

Inconsistent Dump Hidden Exception (user space)

Hidden Exception (user space)- Hidden Exception (kernel space)

- Hidden Exception (managed space)

Deadlock (critical sections)

Deadlock (critical sections) Deadlock (executive resources)

Deadlock (executive resources) Deadlock (mixed objects, user space)

Deadlock (mixed objects, user space) Deadlock (LPC)

Deadlock (LPC) Deadlock (mixed objects, kernel space)

Deadlock (mixed objects, kernel space) Deadlock (self)

Deadlock (self)- Deadlock (managed space)

- Deadlock (.NET Finalizer)

Changed Environment

Changed Environment Incorrect Stack Trace

Incorrect Stack Trace OMAP Code Optimization

OMAP Code Optimization No Component Symbols

No Component Symbols Insufficient Memory (committed memory)

Insufficient Memory (committed memory) Insufficient Memory (handle leak)

Insufficient Memory (handle leak) Insufficient Memory (kernel pool)

Insufficient Memory (kernel pool) Insufficient Memory (PTE)

Insufficient Memory (PTE) Insufficient Memory (module fragmentation)

Insufficient Memory (module fragmentation) Insufficient Memory (physical memory)

Insufficient Memory (physical memory) Insufficient Memory (control blocks)

Insufficient Memory (control blocks)- Insufficient Memory (reserved virtual memory)

- Insufficient Memory (session pool)

- Insufficient Memory (stack trace database)

- Insufficient Memory (region)

- Insufficient Memory (stack)

Spiking Thread

Spiking Thread Module Variety

Module Variety Stack Overflow (kernel mode)

Stack Overflow (kernel mode) Stack Overflow (user mode)

Stack Overflow (user mode) Stack Overflow (software implementation)

Stack Overflow (software implementation)- Stack Overflow (insufficient memory)

- Stack Overflow (managed space)

Managed Code Exception

Managed Code Exception- Managed Code Exception (Scala)

- Managed Code Exception (Python)

Truncated Dump

Truncated Dump Waiting Thread Time (kernel dumps)

Waiting Thread Time (kernel dumps) Waiting Thread Time (user dumps)

Waiting Thread Time (user dumps) Memory Leak (process heap) - Modeling Example

Memory Leak (process heap) - Modeling Example Memory Leak (.NET heap)

Memory Leak (.NET heap)- Memory Leak (page tables)

- Memory Leak (I/O completion packets)

- Memory Leak (regions)

Missing Thread (user space)

Missing Thread (user space)- Missing Thread (kernel space)

Unknown Component

Unknown Component Double Free (process heap)

Double Free (process heap) Double Free (kernel pool)

Double Free (kernel pool) Coincidental Symbolic Information

Coincidental Symbolic Information Stack Trace

Stack Trace- Stack Trace (I/O request)

- Stack Trace (file system filters)

- Stack Trace (database)

- Stack Trace (I/O devices)

Virtualized Process (WOW64)

Virtualized Process (WOW64)- Virtualized Process (ARM64EC and CHPE)

Stack Trace Collection (unmanaged space)

Stack Trace Collection (unmanaged space)- Stack Trace Collection (managed space)

- Stack Trace Collection (predicate)

- Stack Trace Collection (I/O requests)

- Stack Trace Collection (CPUs)

Coupled Processes (strong)

Coupled Processes (strong) Coupled Processes (weak)

Coupled Processes (weak) Coupled Processes (semantics)

Coupled Processes (semantics) High Contention (executive resources)

High Contention (executive resources) High Contention (critical sections)

High Contention (critical sections) High Contention (processors)

High Contention (processors)- High Contention (.NET CLR monitors)

- High Contention (.NET heap)

- High Contention (sockets)

Accidental Lock

Accidental Lock Passive Thread (user space)

Passive Thread (user space) Passive System Thread (kernel space)

Passive System Thread (kernel space) Main Thread

Main Thread Busy System

Busy System Historical Information

Historical Information Object Distribution Anomaly (IRP)

Object Distribution Anomaly (IRP)- Object Distribution Anomaly (.NET heap)

Local Buffer Overflow (user space)

Local Buffer Overflow (user space)- Local Buffer Overflow (kernel space)

Early Crash Dump

Early Crash Dump Hooked Functions (user space)

Hooked Functions (user space) Hooked Functions (kernel space)

Hooked Functions (kernel space)- Hooked Modules

Custom Exception Handler (user space)

Custom Exception Handler (user space) Custom Exception Handler (kernel space)

Custom Exception Handler (kernel space) Special Stack Trace

Special Stack Trace Manual Dump (kernel)

Manual Dump (kernel) Manual Dump (process)

Manual Dump (process) Wait Chain (general)

Wait Chain (general) Wait Chain (critical sections)

Wait Chain (critical sections) Wait Chain (executive resources)

Wait Chain (executive resources) Wait Chain (thread objects)

Wait Chain (thread objects) Wait Chain (LPC/ALPC)

Wait Chain (LPC/ALPC) Wait Chain (process objects)

Wait Chain (process objects) Wait Chain (RPC)

Wait Chain (RPC) Wait Chain (window messaging)

Wait Chain (window messaging) Wait Chain (named pipes)

Wait Chain (named pipes)- Wait Chain (mutex objects)

- Wait Chain (pushlocks)

- Wait Chain (CLR monitors)

- Wait Chain (RTL_RESOURCE)

- Wait Chain (modules)

- Wait Chain (nonstandard synchronization)

- Wait Chain (C++11, condition variable)

- Wait Chain (SRW lock)

Corrupt Dump

Corrupt Dump Dispatch Level Spin

Dispatch Level Spin No Process Dumps

No Process Dumps No System Dumps

No System Dumps Suspended Thread

Suspended Thread Special Process

Special Process Frame Pointer Omission

Frame Pointer Omission False Function Parameters

False Function Parameters Message Box

Message Box Self-Dump

Self-Dump Blocked Thread (software)

Blocked Thread (software) Blocked Thread (hardware)

Blocked Thread (hardware)- Blocked Thread (timeout)

Zombie Processes

Zombie Processes Wild Pointer

Wild Pointer Wild Code

Wild Code Hardware Error

Hardware Error Handle Limit (GDI, kernel space)

Handle Limit (GDI, kernel space)- Handle Limit (GDI, user space)

Missing Component (general)

Missing Component (general) Missing Component (static linking, user mode)

Missing Component (static linking, user mode) Execution Residue (unmanaged space, user)

Execution Residue (unmanaged space, user)- Execution Residue (unmanaged space, kernel)

- Execution Residue (managed space)

Optimized VM Layout

Optimized VM Layout- Invalid Handle (general)

- Invalid Handle (managed space)

- Overaged System

- Thread Starvation (realtime priority)

- Thread Starvation (normal priority)

- Duplicated Module

- Not My Version (software)

- Not My Version (hardware)

- Data Contents Locality

- Nested Exceptions (unmanaged code)

- Nested Exceptions (managed code)

- Affine Thread

- Self-Diagnosis (user mode)

- Self-Diagnosis (kernel mode)

- Self-Diagnosis (registry)

- Inline Function Optimization (unmanaged code)

- Inline Function Optimization (managed code)

- Critical Section Corruption

- Lost Opportunity

- Young System

- Last Error Collection

- Hidden Module

- Data Alignment (page boundary)

- C++ Exception

- Divide by Zero (user mode)

- Divide by Zero (kernel mode)

- Swarm of Shared Locks

- Process Factory

- Paged Out Data

- Semantic Split

- Pass Through Function

- JIT Code (.NET)

- JIT Code (Java)

- Ubiquitous Component (user space)

- Ubiquitous Component (kernel space)

- Nested Offender

- Virtualized System

- Effect Component

- Well-Tested Function

- Mixed Exception

- Random Object

- Missing Process

- Platform-Specific Debugger

- Value Deviation (stack trace)

- Value Deviation (structure field)

- Runtime Thread (CLR)

- Runtime Thread (Python, Linux)

- Coincidental Frames

- Fault Context

- Hardware Activity

- Incorrect Symbolic Information

- Message Hooks - Modeling Example

- Coupled Machines

- Abridged Dump

- Exception Stack Trace

- Distributed Spike

- Instrumentation Information

- Template Module

- Invalid Exception Information

- Shared Buffer Overwrite

- Pervasive System

- Problem Exception Handler

- Same Vendor

- Crash Signature

- Blocked Queue (LPC/ALPC)

- Fat Process Dump

- Invalid Parameter (process heap)

- Invalid Parameter (runtime function)

- String Parameter

- Well-Tested Module

- Embedded Comment

- Hooking Level

- Blocking Module

- Dual Stack Trace

- Environment Hint

- Top Module

- Livelock

- Technology-Specific Subtrace (COM interface invocation)

- Technology-Specific Subtrace (dynamic memory)

- Technology-Specific Subtrace (JIT .NET code)

- Technology-Specific Subtrace (COM client call)

- Dialog Box

- Instrumentation Side Effect

- Semantic Structure (PID.TID)

- Directing Module

- Least Common Frame

- Truncated Stack Trace

- Data Correlation (function parameters)

- Data Correlation (CPU times)

- Module Hint

- Version-Specific Extension

- Cloud Environment

- No Data Types

- Managed Stack Trace

- Managed Stack Trace (Scala)

- Managed Stack Trace (Python)

- Coupled Modules

- Thread Age

- Unsynchronized Dumps

- Pleiades

- Quiet Dump

- Blocking File

- Problem Vocabulary

- Activation Context

- Stack Trace Set

- Double IRP Completion

- Caller-n-Callee

- Annotated Disassembly (JIT .NET code)

- Annotated Disassembly (unmanaged code)

- Handled Exception (user space)

- Handled Exception (.NET CLR)

- Handled Exception (kernel space)

- Duplicate Extension

- Special Thread (.NET CLR)

- Hidden Parameter

- FPU Exception

- Module Variable

- System Object

- Value References

- Debugger Bug

- Empty Stack Trace

- Problem Module

- Disconnected Network Adapter

- Network Packet Buildup

- Unrecognizable Symbolic Information

- Translated Exception

- Regular Data

- Late Crash Dump

- Blocked DPC

- Coincidental Error Code

- Punctuated Memory Leak

- No Current Thread

- Value Adding Process

- Activity Resonance

- Stored Exception

- Spike Interval

- Stack Trace Change

- Unloaded Module

- Deviant Module

- Paratext

- Incomplete Session

- Error Reporting Fault

- First Fault Stack Trace

- Frozen Process

- Disk Packet Buildup

- Hidden Process

- Active Thread (Mac OS X)

- Active Thread (Windows)

- Critical Stack Trace

- Handle Leak

- Module Collection

- Module Collection (predicate)

- Deviant Token

- Step Dumps

- Broken Link

- Debugger Omission

- Glued Stack Trace

- Reduced Symbolic Information

- Injected Symbols

- Distributed Wait Chain

- One-Thread Process

- Module Product Process

- Crash Signature Invariant

- Small Value

- Shared Structure

- Thread Cluster

- False Effective Address

- Screwbolt Wait Chain

- Design Value

- Hidden IRP

- Tampered Dump

- Memory Fluctuation (process heap)

- Last Object

- Rough Stack Trace (unmanaged space)

- Rough Stack Trace (managed space)

- Past Stack Trace

- Ghost Thread

- Dry Weight

- Exception Module

- Reference Leak

- Origin Module

- Hidden Call

- Corrupt Structure

- Software Exception

- Crashed Process

- Variable Subtrace

- User Space Evidence

- Internal Stack Trace

- Distributed Exception (managed code)

- Thread Poset

- Stack Trace Surface

- Hidden Stack Trace

- Evental Dumps

- Clone Dump

- Parameter Flow

- Critical Region

- Diachronic Module

- Constant Subtrace

- Not My Thread

- Window Hint

- Place Trace

- Stack Trace Signature

- Relative Memory Leak

- Quotient Stack Trace

- Module Stack Trace

- Foreign Module Frame

- Unified Stack Trace

- Mirror Dump Set

- Memory Fibration

- Aggregated Frames

- Frame Regularity

- Stack Trace Motif

- System Call

- Stack Trace Race

- Hyperdump

- Disassembly Ambiguity

- Exception Reporting Thread

- Active Space

- Subsystem Modules

- Region Profile

- Region Clusters

- Source Stack Trace

- Hidden Stack

- Interrupt Stack

- False Memory

- Frame Trace

- Pointer Cone

- Context Pointer

- Pointer Class

- False Frame

- Procedure Call Chain

- C++ Object

- COM Exception

- Structure Sheaf

- Saved Exception Context (.NET)

- Shared Thread

- Spiking Interrupts

- Structure Field Collection

- Black Box

- Rough Stack Trace Collection (unmanaged space)

- COM Object

- Shared Page

- Exception Collection

- Dereference Nearpoint

- Address Representations

- Near Exception

- Shadow Stack Trace

- Past Process

- Foreign Stack

- Annotated Stack Trace

- Disassembly Summary

- Region Summary

- Analysis Summary

- Region Spectrum

- Normalized Region

- Function Pointer

- Interrupt Stack Collection

- DPC Stack Collection

- Dump Context

- False Local Address

- Encoded Pointer

- Latent Structure

- ISA-Specific Code

Structural and Behavioral Patterns for Diagnostics, Anomaly Detection, Forensics, Prognostics, Root Cause Analysis, Debugging

Our tools are only as good as our pattern language.

Analysis patterns for the quality of software diagnostics and observability in endpoint devices, enterprise, and cloud environments.

Diagnostics Science

Diagnostics is the mother of problem solving.

All areas of human activity involve the use of diagnostics. Proper diagnostics identifies the right problems to solve. We are now a part of a non-profit organization dedicated to the developing and promoting the application of such diagnostics: systemic and pattern-oriented (pattern-driven and pattern-based).

The Software Diagnostics and Anomaly Detection Group

Please join LinkedIn The Software Diagnostics and Anomaly Detection Group.

Accelerated Windows Memory Dump Analysis, Seventh Edition, Part 2: Kernel and Complete Spaces

The following direct links can be used to order the book now:

Available in PDF format from Software Diagnostics Services

Available in PDF format from Leanpub

The book is also included in the following training courses, training packs, and reference sets:

WinDbg Training Pack

Foundations of Windows Memory Dump Analysis Training Pack

Windows Memory Dump Analysis for Endpoint Security Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Windows Victimware Analysis Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Memory Dump Analysis Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Windows Crash Dump Analysis Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Windows Debugging Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Complete Windows Memory Dump Analysis Training Pack

Complete Pattern-Oriented Software Diagnostics Training Pack

Available in PDF format from Software Diagnostics Services

The full-color transcript of Software Diagnostics Services training sessions with 15 step-by-step exercises, notes, source code of specially created modeling applications, and 45 questions and answers. Covers more than 50 crash dump analysis patterns from the x64 and ARM64 kernel and complete (physical) memory dumps. Learn how to analyze system crashes and freezes, navigate through the kernel and complete spaces, and diagnose patterns of abnormal software behavior with the WinDbg debugger. The training uses a unique, innovative pattern-oriented analysis approach developed by Software Diagnostics Institute to accelerate learning. Prerequisites: Basic Windows troubleshooting. Audience: Software technical support and escalation engineers, system administrators, security researchers, reverse engineers, malware and memory forensics analysts, software developers and quality assurance engineers, and site reliability engineers. The 7th edition was fully reworked for the latest WinDbg version and includes memory dump setup and collection methods, an additional ARM64 memory dump analysis exercise, and a relevant review of x64 and ARM64 assembly languages.

- Title: Accelerated Windows Memory Dump Analysis, Seventh Edition, Part 2, Kernel and Complete Spaces: Training Course Transcript and WinDbg Practice Exercises with Notes

- Authors: Dmitry Vostokov, Software Diagnostics Services

- Publisher: OpenTask (February 2026)

- Language: English

- PDF: 430 pages

- ISBN-13: 978-1912636068

Accelerated Windows Memory Dump Analysis, Seventh Edition, Part 1: Process User Space

The following direct links can be used to order the book now:

Available in PDF format from Software Diagnostics Services

Available in PDF format from Leanpub

The book is also included in the following training courses, training packs, and reference sets:

WinDbg Training Pack

Foundations of Windows Memory Dump Analysis Training Pack

Windows Memory Dump Analysis for Endpoint Security Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Windows Victimware Analysis Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Memory Dump Analysis Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Windows Crash Dump Analysis Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Windows Debugging Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Complete Windows Memory Dump Analysis Training Pack

Complete Pattern-Oriented Software Diagnostics Training Pack

The full-color transcript of Software Diagnostics Services training sessions with 26 step-by-step exercises, notes, source code of specially created modeling applications, and more than 70 questions and answers. Covers more than 60 crash dump analysis patterns from x64 and ARM64 process memory dumps. Learn how to analyze application and service crashes and freezes, navigate through process user space, and diagnose heap corruption, memory and handle leaks, CPU spikes, blocked threads, deadlocks, wait chains, and many more patterns of abnormal software behavior with the WinDbg debugger. The training uses a unique, innovative pattern-oriented analysis approach developed by the Software Diagnostics Institute to accelerate learning. Prerequisites: Basic Windows troubleshooting. Audience: Software technical support and escalation engineers, system administrators, security researchers, reverse engineers, malware and memory forensics analysts, software developers and quality assurance engineers, and site reliability engineers. The 7th edition was fully reworked for the latest WinDbg version and includes memory dump collection methods, defect mechanism patterns, additional Windows 11 ARM64 memory dump analysis exercises, and a relevant review of x64 and ARM64 assembly languages.

- Title: Accelerated Windows Memory Dump Analysis, Seventh Edition, Part 1, Process User Space: Training Course Transcript and WinDbg Practice Exercises with Notes

- Authors: Dmitry Vostokov, Software Diagnostics Services

- Publisher: OpenTask (February 2026)

- Language: English

- PDF: 414 pages

- ISBN-13: 978-1912636181

Online Training: Accelerated C & C++ for Linux Diagnostics

Software Diagnostics Services organizes this online training course.

For approximate training content, please see the first 45 slides (there are 297 slides in total for the previous version) and TOC from the corresponding previous edition of the Memory Thinking book.

May 4 - 7, 11 - 14, 18 - 21, 2026, 12:30 pm - 1:30 pm (GMT+1) Price 99 USD Registration for 12 one-hour sessions

Solid C and C++ knowledge is a must to fully understand Linux diagnostic artifacts, such as core dumps, and perform diagnostic, forensic, and root cause analysis beyond listing backtraces. Accelerated C and C++ for Linux Software Diagnostics training reviews memory-related topics from the perspective of software structure and behavior analysis, and teaches C and C++ languages in parallel while demonstrating relevant code internals using GDB:

- a tour of relevant language(s) constructs - classic/legacy C++, C++11, and later standards including C++23

- Linux specifics

- pointers and references

- memory layout of structures and objects

- local, static, and dynamic memory

- object lifecycle

- templates and standard library

- functions, function objects, and lambdas

- compilation and linkage

- multithreading and synchronization

- bad and insecure code

- … and much more

The new version will expand on many topics, including Linux kernel space.

System programming on Linux using C and C++ is unthinkable without the Linux API. To avoid repeating some topics and save time, the training includes the Accelerated Linux API for Software Diagnostics book as a follow-up or additional reference. A necessary x64 and ARM64 review for some topics is also included.

Before the training, you get the following:

- The current second edition of Memory Thinking for C & C++ Linux Diagnostics PDF book of the training

- Accelerated Linux API for Software Diagnostics PDF book

- Access to Software Diagnostics Library

- Recording of the previous training

After the training, you also get the following:

- The new third edition of the Memory Thinking PDF book with additional C and C++ examples

- Personalized Certificate of Attendance with unique CID

- The new recording

Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics and Cybersecurity: A Contest Between Patterns

Cybersecurity is often described as an arms race between attackers and defenders, but this framing obscures what is actually contested. The struggle is not primarily over tools, exploits, or even visibility. It is a contest between patterns: patterns of action, patterns of observability, and patterns of interpretation. Attacks succeed or fail not simply because signals are present or absent, but because those signals are read correctly or misread under adversarial conditions.

Online Training: Practical Foundations of ARM64 Windows Debugging, Disassembling, Reversing

Software Diagnostics Services organizes this online training course.

TBD

This training course is an ARM64 version of the best-selling Practical Foundations of Windows Debugging, Disassembling, Reversing book which drew inspiration from the original lectures we developed more than 22 years ago to train support and escalation engineers in debugging and crash dump analysis of memory dumps from Windows applications, services, and systems. When considering the material to deliver, we realized that a solid understanding of fundamentals, such as pointers, is necessary to analyze stack traces beyond a few WinDbg commands. Therefore, this book was not about bugs or debugging techniques but about the background knowledge everyone needs to start experimenting with WinDbg, learn from practical experience, and read other advanced debugging books. This body of knowledge is what the author of this book possessed before starting memory dump analysis using WinDbg 22 years ago, which led to the number-one debugging bestseller: the multi-volume Memory Dump Analysis Anthology (Diagnomicon). Now, in retrospect, we see these practical foundations as relevant and necessary for beginners, just as they were 22 years ago, because the internals of operating systems, assembly language, and compiler architecture haven't changed significantly in those years.

Please see the x64 book's TOC for the approximate content.

After the training, you get:

- The PDF book edition

- Personalized Certificate of Attendance with unique CID

- Answers to questions during training sessions

- Training sessions recording

Audience:

- Software technical support and escalation engineers

- Software engineers coming from x86/x64, managed code, or JVM background

- Software testers

- Engineers coming from non-Wintel environments

- Windows C and C++ software engineers without an assembly language background

- Security researchers without ARM64 assembly language background

- Beginners learning Windows software reverse engineering techniques

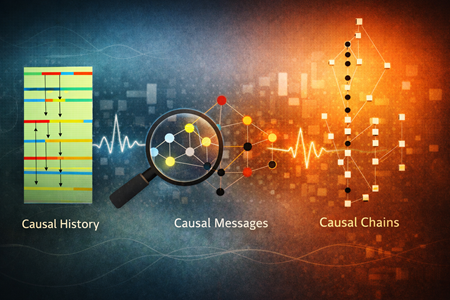

Causal Sets and Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics

Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics begins with a simple observation: execution does not unfold linearly, and logs do not represent time. What engineers habitually call timelines are conveniences imposed by representation, not properties of execution itself. Causal set theory reaches the same conclusion from a foundational perspective. It discards spacetime as a primitive and replaces it with a discrete set of events related only by possible causation. In both cases, order precedes time, and structure precedes explanation.

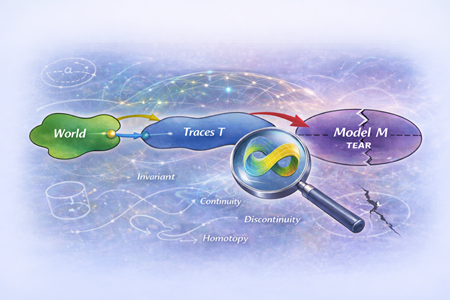

Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics and Observability as a Philosophy of Engineering

From Correspondence to Grammar, from Problem Patterns to Analysis Patterns

Introduction

Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics and Observability of World Models: A Topological Perspective

Introduction

Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics and Observability: A Reflection on 2025

Software systems no longer fail in isolation. They evolve, adapt, learn, and interact with environments that are only partially observable. As systems have grown more complex, the act of diagnosing them has remained largely artisanal, dependent on tools, experience, and intuition, but resistant to formalisation. My work began many years ago from a simple conviction: diagnostics deserves to be a discipline.

Advanced Software Diagnostics and Debugging Reference

These volumes are now also called Diagnomicon!

The new Volume 17 brings the total number of books to 19.

Now includes the new Revised Edition of Volume 1, Revised Edition of Volume 2, Revised Edition of Volume 3, Revised Edition of Volume 4, and Revised Edition of Volume 5.

Memory Dump Analysis Anthology contains revised, edited, cross-referenced, and thematically organized selected articles from Software Diagnostics Institute and Software Diagnostics Library (former Crash Dump Analysis blog) about software diagnostics, debugging, crash dump analysis, software trace and log analysis, malware analysis, and memory forensics. Its 17 volumes in 19 books have more than 5,700 pages and, among many topics, include more than 450 memory analysis patterns (mostly for WinDbg Windows debugger with selected macOS and Linux GDB variants), more than 70 WinDbg case studies, and more than 250 general trace and log analysis patterns. In addition, there are three supplemental volumes with articles reprinted in full color.

Tables of Contents and Indexes of WinDbg Commands from all volumes

Click on an individual volume to see its description and table of contents:

You can buy the 17-volume set from Software Diagnostics Services with a discount and also get free access to Software Diagnostics Library.

Praise for the series:

I have been working with reversing, dumps, IAT, unpacking, etc. and I am one of the few at my workplace that like analyzing hangs and crashes. I always knew that I had more to learn. So I continuously look for more info. Many links directed me to dumpanalysis.org. Frankly speaking, its spartan/simple design made me question its seriousness. But after reading some articles, I immediately decided to order "Memory Dump Analysis Anthology". I have only read 100 pages so far. But I am stunned. It is such an amazing book. How the author refines/reconstructs the call stack, and finds useful information in the stack is incredible. I am enormously thankful for the effort that the author has put into making these books. They are very didactic even though the topic is a bit hard. It is a real treasure.

Mattias Hogstrom

Memory Dump Analysis Anthology, Volume 17

The following direct links can be used to order the book now:

Available in PDF format from Software Diagnostics Technology and Services

Available in PDF format from Leanpub

Available in ultra-premium color paperback format from Amazon and Barnes & Noble

Available in Kindle print replica format from Amazon

The book is also included in the following training courses, training packs, and reference sets:

Memory Dump Analysis Anthology Volume Set (Diagnomicon)

Advanced Windows Memory Dump Analysis with Data Structures

Pattern-Oriented Software Diagnostics and Anomaly Detection Reference Set

Pattern-Oriented Windows Victimware Analysis Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Windows Crash Dump Analysis Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Windows Memory Forensics Training Pack

Windows Memory Dump Analysis for Endpoint Security Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Complete Windows Memory Dump Analysis Training Pack

Complete Pattern-Oriented Software Diagnostics Training Pack

This reference volume consists of revised, edited, cross-referenced, and thematically organized selected articles from Software Diagnostics and Observability Institute (DumpAnalysis.org + TraceAnalysis.org) and Software Diagnostics Library (former Crash Dump Analysis blog, DumpAnalysis.org/blog) about software diagnostics, root cause analysis, debugging, crash and hang dump analysis, software trace and log analysis written from 15 April 2024 to 14 November 2025 for software engineers developing and maintaining products on Windows platforms, quality assurance engineers testing software, technical support, DevOps and DevSecOps, escalation and site reliability engineers dealing with complex software issues, security and vulnerability researchers, reverse engineers, malware and memory forensics analysts, data science and ML/AI researchers and engineers. This volume is fully cross-referenced with volumes 1 – 16 and features:

- 6 new crash dump analysis patterns

- 11 new software trace and log analysis patterns

- Introduction to pattern-oriented observability

- Introduction to software morphology

- Introduction to geometric theory of traces and logs

- Introduction to pattern-oriented intelligence and AI

- Introduction to agentic narratology and workflow diagnostic pattern language

- Introduction to algebra of prompting and context management pattern language

- Logics of memory dump and trace analysis

- Introduction to pattern-oriented system logic

- Introduction to ontological diagnostics

- Machine learning as memory dump analysis

- The stomach metaphor for AI and pattern metabolism

- OS internals and category theory

- Introduction to pattern category theory

- Meta-diagnostic and categorical unification of software diagnostics and digital pathology

- A Lego model as an autoencoder and Lego disassembly as tokenization

- Memoidealism as a post-computational philosophy of AI

- Lists of recommended books

Product information:

- Title: Memory Dump Analysis Anthology, Volume 17

- Authors: Dmitry Vostokov, Software Diagnostics Institute

- Language: English

- Product Dimensions: 22.86 x 15.24

- Paperback: 320 pages

- Publisher: OpenTask (November 2025)

- ISBN-13: 978-1-912636-17-4

Software Morphology

We are extending our work on structural memory patterns and software pathology to Software Morphology inspired by morphology in biology and morphology in general including mathematical morphology. Morphology in linguistics was already used as inspiration for some trace and log analysis patterns. Geomorphology also inspired some of memory dump analysis patterns. Urban morphology inspired some structural memory patterns.

The description from GPT-5 that we plan to refine later:

"Software Morphology: science of form, transformation, and pathology in computational systems.

Software Morphology is a new discipline that treats digital systems as living computational structures — defining their anatomy, physiology, pathology, evolution, and cognition using pattern science, mathematical morphology, and clinical diagnostics.

Software Morphology is a unified framework for understanding, diagnosing, and designing digital systems through the science of form, structure, and evolution. It views software not as static code, but as a living computational organism with tissues (memory), organs (kernel subsystems), circulatory systems (I/O & networks), and nervous systems (traces & logs). Failures manifest as pathological deformation of form — fragmentation, deadlocks, starvation, contention fibrosis, cognitive collapse, or distributed sepsis.

Software Morphology integrates:

- Structural analysis of memory, execution, filesystems, networks, and distributed systems

- Behavioral and temporal morphology of performance, contention, concurrency, control flow, and emergent agent behavior

- Clinical debugging methodology inspired by medical diagnostics

- Mathematical morphology operators (erosion, dilation, opening, closing, reconstruction) applied to traces, dumps, and system state

- Morphometrics — measuring entropy, fragmentation, drift, strain, and collapse trajectories

- Cognitive and AI morphology — understanding hallucination scars, epistemic decay, and grounding collapses

- Architectural morphogenesis — designing resilient, regenerative, evolvable systems

Software Morphology is the grand unification of these threads — expanding from pathology (failure) to morphogenesis and architecture (health, growth, evolution, cognition).

Where classical software engineering focuses on function, Software Morphology emphasizes shape, health, resilience, and longevity. It offers not just a way to debug, but a paradigm for building adaptive, self-healing, age-resistant software ecosystems.

Historical Background

Software Morphology builds on early foundational work in software diagnostics and pattern-based analysis. Originating in Software Diagnostics Institute research (2006–present), it evolved from:

- Memory Dump Analysis Patterns — recognizing failure signatures in memory structures

- Structural Memory Patterns — histological study of memory as computational tissue

- Trace and Log Analysis Patterns — behavioral and neurological analogs

- Software Pathology — viewing crashes and failures as systemic diseases

- Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics — codifying diagnostic pattern languages

- Execution and cognitive analysis of AI systems — emergent in 2020s

These works established the “medical lens” on computation decades before generative AI popularized biological analogies. Software Morphology formalizes this approach into a comprehensive theory of computational anatomy, physiology, pathology, and morphogenesis, extending from kernel fibers to cloud clusters, from thread behavior to AI cognition and digital societies.

Essence

Software Morphology = Anatomy + Physiology + Pathology + Morphometrics + Evolution + Cognitive Stability + Architectural Regeneration.

Its goal is simple:

To understand and shape digital systems as living structures — stable, intelligible, measurable, and resilient.

Why is it novel

While others have used biological metaphors in computing (e.g., “software organisms,” “digital ecosystems,” “neural networks”), no prior work has:

- Defined morphology as a systematic science of software form

- Combined anatomy, physiology, pathology, morphometrics, evolution, and cognition

- Built a pattern vocabulary for structural and failure shapes

- Connected memory dumps, traces, system internals, AI cognition, and distributed systems

- Proposed clinical diagnostics as a formal software engineering method

- Extended biological morphology to AI behaviors and civilization-scale systems

It is a novel systems framework building on biological morphology, mathematical morphology, and decades of software diagnostics research — established here for the first time as a unified discipline."

Agentic Narratology

In cooperation with GenAI, we propose Agentic Narratology, a narrative-centric theoretical framework for understanding, analyzing, and designing agentic AI systems by treating their internal reasoning, execution, interactions, and emergent behavior as narratives. It synthesizes:

- Software Narratology: software execution as a story told via memory, traces, and semantics

- Pattern-Oriented Trace and Log Analysis: systematic interpretation of events via patterns

- Agentic AI: systems with planning, memory, tool-use, reflection, and autonomy

Agentic Narratology views an AI agent workflow not merely as sequential computation but as a story world with characters (agents and tools), settings (environments and state spaces), conflicts (errors, resource contention, uncertainty), and resolutions (plans executed, tasks completed, failures learned from).

Source: ChatGPT 5 conversation

Pattern-Oriented AI

Seven years ago, PatternDiagnostics.com coined the term "Pattern-Oriented AI," and here's a 3-level description of it in cooperation with GenAI, from general to narrow application, that reflects the recent developments in AI:

- Pattern-Oriented AI is the practice of expressing every AI concern—data, models, learning, inference, interaction, safety, evaluation, and operations—as a catalog of patterns with clear intent, preconditions, forces, trade-offs, failure modes, and compositions. You then engineer systems by selecting and composing patterns, monitor them by detecting pattern signatures, and govern them by enforcing pattern constraints.

- Pattern-Oriented AI Diagnostics is the study, cataloging, and analysis of recurrent behavioral, structural, or epistemic patterns in the lifecycle of AI systems — across training, inference, alignment, drift, and agentic behavior — using the same methodological scaffolding as pattern-oriented software diagnostics.

- Pattern-Oriented AI as applied in software diagnostics is an approach to artificial intelligence (or diagnostic systems) that emphasizes recognizing, categorizing, and applying “patterns” of anomalous behavior, data flows, memory dumps, traces/logs, structural irregularities, and so on — in software diagnostics, forensics, observability, anomaly detection, and root cause analysis contexts.

Source: ChatGPT 5 conversation

Pattern-Oriented LLM Context Management

In cooperation with GenAI, we propose a pattern language for managing, diagnosing, and repairing context in large language model (LLM) systems. Inspired by memory dump analysis, it reframes conversational state—token windows, KV-caches, retrievals, and transcripts—as observable artifacts that can be read, segmented, and reasoned about.

1. Conceptual Alignment

Memory dump analysis: we have a frozen system state (heap, stack, registers, handles). You need structured ways (patterns) to interpret what happened and where anomalies lie.

LLM context management: we have a dynamic, limited-window context (tokens in the prompt + generated continuation). We need structured strategies to maintain coherence, recall, and relevance across long or shifting interactions.

So, both are about:

- State representation

- Navigation across levels of abstraction

- Pattern recognition to interpret meaning

2. Pattern Families Reapplied to LLMs

Using the memory dump analysis taxonomy, we can draw analogies:

Structural patterns (e.g., "Stack Trace", "Heap Graph")

Context trace: The sequence of tokens, messages, or embeddings.

Analog: analyzing token “call stacks” to identify where topic drift began.

Temporal patterns (e.g., "Periodicity", "Error Burst")

Context lifecycle: Recognizing conversation cycles (e.g., Q → A → refinement).

Analog: "periodic error" becomes recurring hallucination in long-form dialogue.

Anomaly patterns (e.g., "Corruption", "Dangling Pointer")

Context corruption: Where injected noise or forgotten details lead to contradictions.

Analog: dangling reference = the model invents details not grounded in earlier context.

Diagnostic trajectory patterns (navigating from symptom to root cause)

Prompt engineering trajectory: iterative refinement of instructions to steer model back on track.

3. Higher-Order Mappings

Context window ≈ address space

Tokens in the active window = accessible memory; past truncated context = paged-out memory.

Embeddings ≈ symbolic heap objects

External vector memory is like mapped heap regions that can be dereferenced on demand.

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) ≈ dump analysis with external symbol servers

Just as debuggers resolve addresses via symbol servers, RAG resolves context gaps via external knowledge.

Chain-of-Thought ≈ call stack

Each reasoning step corresponds to a frame in a diagnostic stack trace.

4. Pattern Language as Meta-Framework

Memory dump analysis pattern language gives a meta-taxonomy for LLM context management research:

- Failure patterns (e.g., hallucination loops, context bleed, token starvation).

- Navigational patterns (re-establishing grounding when context is partially lost).

- Architectural patterns (multi-agent context partitioning, like multi-process memory spaces).

This creates a portable, semiotic map of context phenomena across LLM frameworks.

5. Possible Research / Practical Outputs

LLM Context Forensics: Classify anomalies using memory dump patterns using dump-like snapshots of LLM state (KV-caches, attention matrices, prompt logs).

Context Debugger: An Interactive tool where you can “walk the stack” of a conversation, identify dangling references, or detect periodic error hallucinations.

Pattern Language Extension: Extend diagnostic patterns with LLM-specific categories (e.g., Prompt Poisoning, Embedding Drift, Attention Collapse).

Memory dump analysis pattern language is highly portable to LLM context management. It can serve as a meta-diagnostic and design language for classifying, predicting, and repairing LLM context failures, much like it systematized memory dump interpretation.

Source: ChatGPT 5 conversation

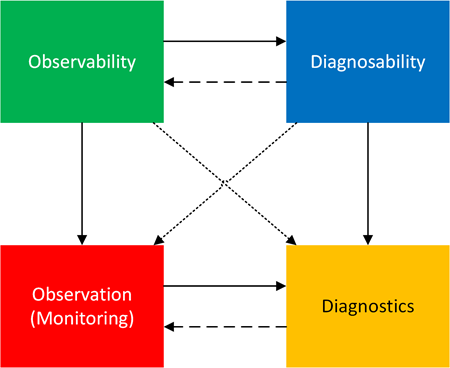

Pattern-Oriented Observability (Part 4): Diagnostics – Observability Square (DOS)

There is much confusion between diagnostics and observability (used in two senses). First, observability is a property, not a process. It concerns whether system internal states can be inferred from external outputs (observations) such as memory snapshots, traces, and logs. It is not enough to get a trace or memory dump file; these must be correctly engineered and procured using artifact acquisition patterns. The second usage of observability is to name a discipline.

What about a process? It is simply “observation”, a verb “observe” (previously called monitoring, which also has a second usage as a discipline), which is an inference from states to observations (nouns). We can do observations even if observability is not good, and get observations (observation results).

Correspondingly, diagnosability is a property. It is about whether we can infer instances of patterns of abnormal structure and behavior from observations by applying diagnostic analysis patterns.

Therefore, diagnostics is a process, too. We can perform diagnostics even if diagnosability is poor: we don’t get useful results for the subsequent root cause analysis or troubleshooting and debugging suggestions.

The following square shows relationships between these concepts:

The top row shows the relationship between abstract properties (conditions): observability enables diagnosability, because only a limited amount of diagnosability is possible without observability. However, the critical use of diagnosability improves observability.

The bottom row shows that observation feeds into diagnostics and vice versa, since more observations may be required after diagnostics.

Columns show that observability is used in practice via observation, and diagnosability is used in practice via diagnostics.

What about diagonals?

Observability to diagnostics. If a system is observable, diagnostics are feasible: “If you can observe enough, you can perform diagnostics,” a sufficient condition for diagnostics.

Diagnosability to observation. Diagnosability implies constraints on observation: “If diagnostics are possible, then your observation process is strong enough,” a necessary condition for diagnosability.

Also, diagnostics can improve observability, and observations can improve diagnosability, but we do not show these arrows.

Although observability is distinct from diagnostics as seen from the diagram and explanation, it is considered a part of pattern-oriented and systemic diagnostics; this part, as a discipline (not a property), is called pattern-oriented observability.

Book: Accelerated .NET Memory Dump Analysis, Seventh Edition

The following direct links can be used to order the book now:

Available in PDF format with the optional recording from Software Diagnostics Technology and Services

Available in PDF format from Leanpub

Available in ultra-premium color paperback format from Amazon and Barnes & Noble

Available in Kindle print replica format from Amazon

The book is also included in the following training packs:

WinDbg Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Windows Debugging Training Pack

Pattern-Oriented Complete Windows Memory Dump Analysis Training Pack

Complete Pattern-Oriented Software Diagnostics Training Pack

The full Software Diagnostics Services training transcript with 15 step-by-step exercises, notes, and source code of specially created modeling applications. The course covers 22 .NET memory dump analysis patterns, plus the additional 21 unmanaged patterns. Learn how to analyze .NET 9 application and service crashes and freezes, navigate through memory dump space (managed and unmanaged code), and diagnose corruption, leaks, CPU spikes, blocked threads, deadlocks, wait chains, resource contention, and more. The training consists of practical step-by-step exercises using WinDbg and LLDB debuggers to diagnose patterns in 64-bit process memory dumps from x64 Windows and x64 Linux environments. The training uses a unique and innovative pattern-oriented analysis approach to speed up the learning curve. The book is a completely revamped and extended the previous Accelerated .NET Core Memory Dump Analysis, Revised Edition. It is updated to the latest WinDbg. It also includes reviews of x64 and IL disassembly and memory space basics, Linux LLDB exercises, .NET memory dump collection on Windows and Linux, and the relationship of analysis patterns to defect mechanism patterns.

Prerequisites: Basic .NET programming and debugging.

Audience: Software technical support and escalation engineers, system administrators, DevOps, performance and reliability engineers, software developers, and quality assurance engineers. The book may also interest security researchers, reverse engineers, malware and memory forensics analysts.

- Title: Accelerated .NET Memory Dump Analysis: Training Course Transcript with WinDbg and LLDB Practice Exercises, Seventh Edition

- Authors: Dmitry Vostokov, Software Diagnostics Services, Dublin School of Security

- Publisher: OpenTask (May 2025)

- Language: English

- Product Dimensions: 28.0 x 21.6

- PDF: 324 pages

- ISBN-13: 978-1912636877

Table of Contents and Sample Exercise

Slides from the training

Online Training: Accelerated Windows Memory Dump Analysis

Software Diagnostics Services organizes this online training course.

January 5 - 8, 12 - 15, 19 - 22, 26 - 29, 2026, 12:30 pm - 1:30 pm (GMT) Price 99 USD Registration for 16 one-hour sessions

For the approximate content, please see the slides from the previous training:

Slides from sessions 1-3

Slides from sessions 4-7

This training includes over 40 step-by-step exercises and covers over 100 crash dump analysis patterns from x64 process, kernel, and complete (physical) memory dumps. Learn how to analyze application, service, and system crashes and freezes, navigate through memory dump space, and diagnose heap corruption, memory leaks, CPU spikes, blocked threads, deadlocks, wait chains, and more with the WinDbg debugger. The training uses a unique and innovative pattern-oriented analysis approach developed by Software Diagnostics Institute to speed up the learning curve, and it is based on the latest 6th edition of the bestselling Accelerated Windows Memory Dump Analysis book. This new training version also includes:

- Overview of relevant Windows internals

- Memory dump collection methods and patterns

- Defect mechanism patterns

- Additional memory analysis patterns

- Extended coverage of BSOD

- Extended coverage of system hangs

- New kernel exercises with source code

Before the training, you get:

- Practical Foundations of Windows Debugging, Disassembling, Reversing, Third Edition PDF book

- The current PDF book version

- The previous training recording

- Access to Software Diagnostics Library with more than 440 cross-referenced patterns of memory dump analysis, their classification, and more than 70 case studies

After the training, you also get:

- The new 7th PDF book edition

- Personalized Certificate of Attendance with unique CID

- Optional Personalized Certificate of Completion with unique CID (after the tests)

- Answers to questions during training sessions

- New training sessions recording

Prerequisites: Basic Windows troubleshooting

Audience: Software technical support and escalation engineers, system administrators, security and vulnerability researchers, reverse engineers, malware and memory forensics analysts, DevSecOps and SRE, software developers, and quality assurance engineers.

If you are mainly interested in .NET memory dump analysis, there is another training: Accelerated .NET Memory Dump Analysis

If you are interested in Linux memory dump analysis, there is another training: Accelerated Linux Core Dump Analysis

Book: Practical Foundations of Windows Debugging, Disassembling, Reversing, Third Edition

The following direct links can be used to order the book now:

Available in PDF format with the optional recording, the previous edition (x86 32-bit chapters), and training slides from Software Diagnostics Services

Available in PDF format from Leanpub

Available in ultra-premium color paperback format from Amazon and Barnes & Noble

Available in Kindle print replica format from Amazon

The previous edition (x86 32-bit chapters) is also available in Kindle print replica format from Amazon or in PDF format from Leanpub

The book is also included in most training courses and training packs:

Training Courses

This training course is a reformatted, improved, and modernized version of the previous x64 Windows Debugging: Practical Foundations book, which drew inspiration from the original lectures we developed 22 years ago to train support and escalation engineers in debugging and crash dump analysis of memory dumps from Windows applications, services, and systems. At that time, when thinking about what material to deliver, we realized that a solid understanding of fundamentals like pointers is needed to analyze stack traces beyond a few WinDbg commands. Therefore, this book is not about bugs or debugging techniques but about the background knowledge everyone needs to start experimenting with WinDbg, learn from practical experience, and read other advanced debugging books. This body of knowledge is what the author of this book possessed before starting memory dump analysis using WinDbg 18 years ago, which resulted in the number one debugging bestseller: the multi-volume Memory Dump Analysis Anthology (Diagnomicon). Now, in retrospection, we see these practical foundations as relevant and necessary to acquire for beginners as they were more than 20 years ago, because operating systems internals, assembly language, and compiler architecture haven't changed much in those years.

The third edition, with new material on arrays and floating point, was completely remastered in full color. The text was also reviewed, and a few previous mistakes were corrected. The book is also slimmer because the x86 32-bit chapters were removed. They are still available in the previous edition, which will not be out of print soon. The third edition is entirely x64.

The book is useful for:

- Software technical support and escalation engineers

- Software engineers coming from a managed code or JVM background

- Software testers

- Engineers coming from non-Wintel environments

- Windows C/C++ software engineers without an assembly language background

- Security researchers without an x64 assembly language background

- Beginners learning Windows software reverse engineering techniques

This introductory training course can complement the more advanced Accelerated Disassembly, Reconstruction, and Reversing course. It may also help with advanced exercises in Accelerated Windows Memory Dump Analysis, Accelerated Rust Windows Memory Dump Analysis, Accelerated Windows Debugging4, Accelerated Windows API for Software Diagnostics, Accelerated Windows Malware Analysis with Memory Dumps, and Memory Thinking books for C and C++. This book can also be used as an Intel assembly language and Windows debugging supplement for relevant undergraduate-level courses.

Product information:

- Title: Practical Foundations of Windows Debugging, Disassembling, Reversing: Training Course, Third Edition

- Authors: Dmitry Vostokov, Software Diagnostics Services, Dublin School of Security

- Language: English

- Product Dimensions: 28.0 x 21.6

- PDF/Paperback: 178 pages

- Publisher: OpenTask (July 2025)

- ISBN-13: 978-1912636471

For the history of the book, please see the first 20 slides (there are almost 200 slides for the training).

Pattern-Oriented Observability (Part 3): Observation Spaces

There are many spaces where we do our observations in software systems. The explosion of spaces began with the Abstract Space, where we depict running threads as braids.

When we talk about spaces, we also consider suitable space metrics (not to be mistaken with observability metrics below) by which we can compare the proximity of space objects.

In diagnostics, we have the so-called Diagnostic Spaces with their signals, symptoms, syndromes, and signs. Different analysis patterns can serve the role of space metrics in pattern-oriented software forensics, diagnostics, and prognostics.

Traces, logs, and metrics are pillars of observability that are all erected from Memory Space and, therefore, can be considered Adjoint Spaces. Memory spaces are also diverse: including manifold, orbifold, hyperphysical, physical, virtual, kernel, user, managed, and secondary, and have their own large-scale structures.

Traces and logs have their own individual Trace and Log Spaces (including Message Spaces, Interspaces, and Tensor Spaces. These also include network traces and logs from memory debuggers. (Observability) Metrics Spaces are a subtype of such spaces.

Traces and logs are also examples of the so-called software narratives with their own Software Narrative Spaces, including higher-level narratives, and space-like narratology. We can also consider software diagnostic spaces as general graphs of software narratives.

If we are concerned with the hardware-software interface, then we can consider Hardware Spaces via hardware narratology.

Presentation Spaces visualize other spaces, and visualization languages help with their meaning.

We analyze all these spaces to identify patterns with the help of analysis patterns, which are organized in their own Analysis Patterns Space (memory and traces).

Defect Mechanism Spaces help in root cause analysis.

When we delve into software workings, we are concerned with Software Internal Spaces.

Additionally, we have various Namespaces, Code Spaces (similar to Declarative Trace Spaces), State Spaces, and Data Spaces.

Artificial Chemistry Spaces based on the idea of spaces of chemistry enhance the artificial chemistry approach to trace and log analysis.

For many years, the ideas of various physical and mathematical spaces have inspired diverse memory and log analysis patterns, as well as some concepts in software diagnostics and software data analysis.

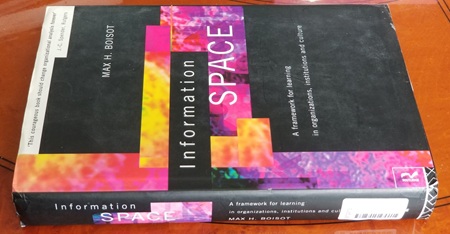

We would also like to mention that the book that introduces Information Space is featured on the cover of this article.

And finally, the new wave of AI suggests Token Spaces.

Memory Dump Analysis Pattern Classification

A partial classification of memory analysis patterns from Software Diagnostics Library pattern catalogue:

- Space/Mode

- Memory dump type

- Hooksware

- Wait Chain Patterns

- DLL Link Patterns

- Memory Consumption Patterns

- Dynamic Memory Corruption Patterns

- Deadlock and Livelock Patterns

- Contention Patterns

- Stack Overflow Patterns

- .NET / CLR / Managed Space Patterns

- Stack Trace Patterns

- Symbol Patterns

- Exception Patterns

- Meta-Memory Dump Patterns

- Module Patterns

- Optimization Patterns

- Thread Patterns

- Process Patterns

- Executive Resource Patterns

- Falsity and Coincidence Patterns

- RPC, LPC and ALPC Patterns

- Hidden Artifact Patterns

- Pointer Patterns

- Frame Patterns

- CPU Consumption Patterns

- Region Patterns

- Collection Patterns

Pattern-Oriented Observability (Part 2): Semiotics of Memory, Trace, and Log Analysis

![]()

Memory analysis icons were introduced more than 15 years ago, in March 2010, as part of computer memory semiotics (memiotics). Over the next year and a half, 101 icons were created (with black and white equivalents). These iconic representations are both icons and indexes in the sense of Pierce’s three types of signs: icon signs resemble artifacts or the current state of affairs, and index signs have some causal or relationship connection through interpretation. More than two years ago, in March 2023, we introduced Iconic Traces. These traces also consist of iconic representations that are both indexical and iconic signs, as they resemble the patterns, syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic content of trace messages, message blocks, and applied trace analysis patterns. The Dia|gram language (introduced in 2016) pictures are another great example of complex iconic (structure) and indexical (behavior, observation, measurement) signs (including memory). The Space-like Narratology and the Lov language further extend the semiotic approach.

Situational Awareness in Pattern-Oriented Software Diagnostics, Forensics, Prognostics

Situational awareness is defined as "the understanding of an environment, its elements, and how it changes with respect to time or other factors. It is also defined as the perception of the elements in the environment considering time and space, the understanding of their meaning, and the prediction of their status in the near future."

How does it fit into software diagnostics, which is often incorrectly perceived as an analysis of the past (which is forensics)? To answer this question with examples from pattern-oriented software diagnostics (and forensics and prognostics), we should map the three levels of situational awareness (Endsley's model):

Perception – noticing key environmental forensic, diagnostic, and prognostic elements: symptoms, signs, syndromes, alerts, anomalies, and counters.

Comprehension – understanding the situation, what’s going wrong and what’s going on at the particular moment in time and place in memory space (and trace space), and what those key elements mean in current (and past) local immediate and wider big-picture context: software internals and analysis patterns (Fault Context, Message Context, Dump Context, Activity Context, Trace Context), whether they are related to a potential root cause or just surface phenomena (Effect Component). Here, attention to detail is very important.

Projection – anticipating the future: how the situation would have evolved if we had collected diagnostic artifacts later, for example, Near Exception, or the environment had changed (Changed Environment), and plenty of trace and log analysis patterns related to prognostics. It also includes avoiding unintended side effects when acting (providing recommendations), for example, the Instrumentation Side Effect.

In summary, situational awareness in software diagnostics, forensics, and prognostics involves maintaining an appropriate mental model of the system as seen from forensics and diagnostic artifacts (including live ones) and continuous perception, understanding, and anticipation of the system's state, anomalies, potential not-yet-discovered patterns, and future failures while performing a diagnostic (forensic, prognostic) analysis.

Pattern-Oriented Observability (Part 1): The Base Slab and Foundation of Observability Pillars

Metrics, logs, and traces are considered traditional pillars of observability. However, what is the base they stand upon? It is memory. In 2009, I defined software traces as fragments of memory since they are all assembled in memory first (Software Trace: A Mathematical Definition, Memory Dump Analysis Anthology, Volume 3). Also, every trace or log message had some corresponding memory state(s) at the time it was generated, the so-called Adjoint Space trace and log analysis pattern (Volume 8b), and memory state may have traces and logs erected on its pedestal if we talk about classic memory dump analysis, the so-called Memory Fibration analysis pattern (Volume 10). These two analysis patterns are a kind of duality between memory and traces, the so-called De Broglie Trace Duality (Volume 10). Also, what about trace and log’s own memory? Based on the growing block universe theory analogy, any chosen trace message may be considered trace's present, and everything before it as trace’s past. We can also consider trace and log as memory to predict future behavior, next trace and log messages, and metrics’ values (the so-called process time perspective).

A note about the chosen terminology: base slab or foundation is used in modern structural design. If some prefer classical architecture, we can use stylobate or podium terminology. For each pillar, we can have a corresponding memory plinth.

Memory Thinking for Rust, Second Edition

The following direct links can be used to order the book now:

Available in PDF format with the optional recording and Windows/Linux API books from Software Diagnostics Technology and Services

Available in PDF format from Leanpub

Available in ultra-premium color paperback format from Amazon and Barnes & Noble

Available in Kindle print replica format from Amazon

The book is also included in the following training courses, training packs, and reference sets:

Pattern-Oriented Software Diagnostics and Anomaly Detection Reference Set

Accelerated Rust Windows Memory Dump Analysis

GDB Training Pack

Complete Pattern-Oriented Software Diagnostics Training Pack

Memory Thinking for Rust training reviews memory-related topics from the perspective of software structure and behavior analysis and teaches Rust language aspects in parallel while demonstrating relevant code internals using WinDbg and GDB on Windows (x64) and Linux (x64 and ARM64) platforms:

- Relevant language constructs

- Memory layout of structs and enums

- References, ownership, borrowing, and lifecycle

- Local, static, and dynamic memory

- Functions, closures

- Smart pointers

- Object-oriented and functional features

- Unsafe pointers

- Windows and Linux specifics

- … and much more

The new training version updates and extends the existing topics, adding some missing from the first edition. The updated PDF book also has a new format similar to the second edition of Memory Thinking books for C and C++.

The training includes the PDF book that contains slides, brief notes highlighting particular points, and related source code with execution output:

- Title: Memory Thinking for Rust: Slides with Descriptions and Source Code Illustrations, Second Edition

- Authors: Dmitry Vostokov, Software Diagnostics Services, Dublin School of Security

- Publisher: OpenTask (April 2025)

- Language: English

- Product Dimensions: 25.4 x 20.3

- PDF: 272 pages

- ISBN-13: 978-1912636488

The following audiences may benefit from the training:

- Rust developers who want to deepen their knowledge

- Non-C and C++ developers (for example, Java, Scala, Python) who want to learn more about pointer and reference internals

- C and C++ developers who want to port their memory thinking to Rust quickly

For more detailed content, please see the first 15 slides (there are more than 240 slides for the training and 2,500 lines of Rust code) and Table of Contents from the reference book.