Multiple Exceptions (user mode) - Modeling Example

Multiple Exceptions (user mode) - Modeling Example Multiple Exceptions (kernel mode)

Multiple Exceptions (kernel mode) Multiple Exceptions (managed space)

Multiple Exceptions (managed space)- Multiple Exceptions (stowed)

Dynamic Memory Corruption (process heap)

Dynamic Memory Corruption (process heap) Dynamic Memory Corruption (kernel pool)

Dynamic Memory Corruption (kernel pool)- Dynamic Memory Corruption (managed heap)

False Positive Dump

False Positive Dump Lateral Damage (general)

Lateral Damage (general)- Lateral Damage (CPU mode)

Optimized Code (function parameter reuse)

Optimized Code (function parameter reuse) Invalid Pointer (general)

Invalid Pointer (general)- Invalid Pointer (objects)

NULL Pointer (code)

NULL Pointer (code) NULL Pointer (data)

NULL Pointer (data) Inconsistent Dump

Inconsistent Dump Hidden Exception (user space)

Hidden Exception (user space)- Hidden Exception (kernel space)

- Hidden Exception (managed space)

Deadlock (critical sections)

Deadlock (critical sections) Deadlock (executive resources)

Deadlock (executive resources) Deadlock (mixed objects, user space)

Deadlock (mixed objects, user space) Deadlock (LPC)

Deadlock (LPC) Deadlock (mixed objects, kernel space)

Deadlock (mixed objects, kernel space) Deadlock (self)

Deadlock (self)- Deadlock (managed space)

- Deadlock (.NET Finalizer)

Changed Environment

Changed Environment Incorrect Stack Trace

Incorrect Stack Trace OMAP Code Optimization

OMAP Code Optimization No Component Symbols

No Component Symbols Insufficient Memory (committed memory)

Insufficient Memory (committed memory) Insufficient Memory (handle leak)

Insufficient Memory (handle leak) Insufficient Memory (kernel pool)

Insufficient Memory (kernel pool) Insufficient Memory (PTE)

Insufficient Memory (PTE) Insufficient Memory (module fragmentation)

Insufficient Memory (module fragmentation) Insufficient Memory (physical memory)

Insufficient Memory (physical memory) Insufficient Memory (control blocks)

Insufficient Memory (control blocks)- Insufficient Memory (reserved virtual memory)

- Insufficient Memory (session pool)

- Insufficient Memory (stack trace database)

- Insufficient Memory (region)

- Insufficient Memory (stack)

Spiking Thread

Spiking Thread Module Variety

Module Variety Stack Overflow (kernel mode)

Stack Overflow (kernel mode) Stack Overflow (user mode)

Stack Overflow (user mode) Stack Overflow (software implementation)

Stack Overflow (software implementation)- Stack Overflow (insufficient memory)

- Stack Overflow (managed space)

Managed Code Exception

Managed Code Exception- Managed Code Exception (Scala)

- Managed Code Exception (Python)

Truncated Dump

Truncated Dump Waiting Thread Time (kernel dumps)

Waiting Thread Time (kernel dumps) Waiting Thread Time (user dumps)

Waiting Thread Time (user dumps) Memory Leak (process heap) - Modeling Example

Memory Leak (process heap) - Modeling Example Memory Leak (.NET heap)

Memory Leak (.NET heap)- Memory Leak (page tables)

- Memory Leak (I/O completion packets)

- Memory Leak (regions)

Missing Thread (user space)

Missing Thread (user space)- Missing Thread (kernel space)

Unknown Component

Unknown Component Double Free (process heap)

Double Free (process heap) Double Free (kernel pool)

Double Free (kernel pool) Coincidental Symbolic Information

Coincidental Symbolic Information Stack Trace

Stack Trace- Stack Trace (I/O request)

- Stack Trace (file system filters)

- Stack Trace (database)

- Stack Trace (I/O devices)

Virtualized Process (WOW64)

Virtualized Process (WOW64)- Virtualized Process (ARM64EC and CHPE)

Stack Trace Collection (unmanaged space)

Stack Trace Collection (unmanaged space)- Stack Trace Collection (managed space)

- Stack Trace Collection (predicate)

- Stack Trace Collection (I/O requests)

- Stack Trace Collection (CPUs)

Coupled Processes (strong)

Coupled Processes (strong) Coupled Processes (weak)

Coupled Processes (weak) Coupled Processes (semantics)

Coupled Processes (semantics) High Contention (executive resources)

High Contention (executive resources) High Contention (critical sections)

High Contention (critical sections) High Contention (processors)

High Contention (processors)- High Contention (.NET CLR monitors)

- High Contention (.NET heap)

- High Contention (sockets)

Accidental Lock

Accidental Lock Passive Thread (user space)

Passive Thread (user space) Passive System Thread (kernel space)

Passive System Thread (kernel space) Main Thread

Main Thread Busy System

Busy System Historical Information

Historical Information Object Distribution Anomaly (IRP)

Object Distribution Anomaly (IRP)- Object Distribution Anomaly (.NET heap)

Local Buffer Overflow (user space)

Local Buffer Overflow (user space)- Local Buffer Overflow (kernel space)

Early Crash Dump

Early Crash Dump Hooked Functions (user space)

Hooked Functions (user space) Hooked Functions (kernel space)

Hooked Functions (kernel space)- Hooked Modules

Custom Exception Handler (user space)

Custom Exception Handler (user space) Custom Exception Handler (kernel space)

Custom Exception Handler (kernel space) Special Stack Trace

Special Stack Trace Manual Dump (kernel)

Manual Dump (kernel) Manual Dump (process)

Manual Dump (process) Wait Chain (general)

Wait Chain (general) Wait Chain (critical sections)

Wait Chain (critical sections) Wait Chain (executive resources)

Wait Chain (executive resources) Wait Chain (thread objects)

Wait Chain (thread objects) Wait Chain (LPC/ALPC)

Wait Chain (LPC/ALPC) Wait Chain (process objects)

Wait Chain (process objects) Wait Chain (RPC)

Wait Chain (RPC) Wait Chain (window messaging)

Wait Chain (window messaging) Wait Chain (named pipes)

Wait Chain (named pipes)- Wait Chain (mutex objects)

- Wait Chain (pushlocks)

- Wait Chain (CLR monitors)

- Wait Chain (RTL_RESOURCE)

- Wait Chain (modules)

- Wait Chain (nonstandard synchronization)

- Wait Chain (C++11, condition variable)

- Wait Chain (SRW lock)

Corrupt Dump

Corrupt Dump Dispatch Level Spin

Dispatch Level Spin No Process Dumps

No Process Dumps No System Dumps

No System Dumps Suspended Thread

Suspended Thread Special Process

Special Process Frame Pointer Omission

Frame Pointer Omission False Function Parameters

False Function Parameters Message Box

Message Box Self-Dump

Self-Dump Blocked Thread (software)

Blocked Thread (software) Blocked Thread (hardware)

Blocked Thread (hardware)- Blocked Thread (timeout)

Zombie Processes

Zombie Processes Wild Pointer

Wild Pointer Wild Code

Wild Code Hardware Error

Hardware Error Handle Limit (GDI, kernel space)

Handle Limit (GDI, kernel space)- Handle Limit (GDI, user space)

Missing Component (general)

Missing Component (general) Missing Component (static linking, user mode)

Missing Component (static linking, user mode) Execution Residue (unmanaged space, user)

Execution Residue (unmanaged space, user)- Execution Residue (unmanaged space, kernel)

- Execution Residue (managed space)

Optimized VM Layout

Optimized VM Layout- Invalid Handle (general)

- Invalid Handle (managed space)

- Overaged System

- Thread Starvation (realtime priority)

- Thread Starvation (normal priority)

- Duplicated Module

- Not My Version (software)

- Not My Version (hardware)

- Data Contents Locality

- Nested Exceptions (unmanaged code)

- Nested Exceptions (managed code)

- Affine Thread

- Self-Diagnosis (user mode)

- Self-Diagnosis (kernel mode)

- Self-Diagnosis (registry)

- Inline Function Optimization (unmanaged code)

- Inline Function Optimization (managed code)

- Critical Section Corruption

- Lost Opportunity

- Young System

- Last Error Collection

- Hidden Module

- Data Alignment (page boundary)

- C++ Exception

- Divide by Zero (user mode)

- Divide by Zero (kernel mode)

- Swarm of Shared Locks

- Process Factory

- Paged Out Data

- Semantic Split

- Pass Through Function

- JIT Code (.NET)

- JIT Code (Java)

- Ubiquitous Component (user space)

- Ubiquitous Component (kernel space)

- Nested Offender

- Virtualized System

- Effect Component

- Well-Tested Function

- Mixed Exception

- Random Object

- Missing Process

- Platform-Specific Debugger

- Value Deviation (stack trace)

- Value Deviation (structure field)

- Runtime Thread (CLR)

- Runtime Thread (Python, Linux)

- Coincidental Frames

- Fault Context

- Hardware Activity

- Incorrect Symbolic Information

- Message Hooks - Modeling Example

- Coupled Machines

- Abridged Dump

- Exception Stack Trace

- Distributed Spike

- Instrumentation Information

- Template Module

- Invalid Exception Information

- Shared Buffer Overwrite

- Pervasive System

- Problem Exception Handler

- Same Vendor

- Crash Signature

- Blocked Queue (LPC/ALPC)

- Fat Process Dump

- Invalid Parameter (process heap)

- Invalid Parameter (runtime function)

- String Parameter

- Well-Tested Module

- Embedded Comment

- Hooking Level

- Blocking Module

- Dual Stack Trace

- Environment Hint

- Top Module

- Livelock

- Technology-Specific Subtrace (COM interface invocation)

- Technology-Specific Subtrace (dynamic memory)

- Technology-Specific Subtrace (JIT .NET code)

- Technology-Specific Subtrace (COM client call)

- Dialog Box

- Instrumentation Side Effect

- Semantic Structure (PID.TID)

- Directing Module

- Least Common Frame

- Truncated Stack Trace

- Data Correlation (function parameters)

- Data Correlation (CPU times)

- Module Hint

- Version-Specific Extension

- Cloud Environment

- No Data Types

- Managed Stack Trace

- Managed Stack Trace (Scala)

- Managed Stack Trace (Python)

- Coupled Modules

- Thread Age

- Unsynchronized Dumps

- Pleiades

- Quiet Dump

- Blocking File

- Problem Vocabulary

- Activation Context

- Stack Trace Set

- Double IRP Completion

- Caller-n-Callee

- Annotated Disassembly (JIT .NET code)

- Annotated Disassembly (unmanaged code)

- Handled Exception (user space)

- Handled Exception (.NET CLR)

- Handled Exception (kernel space)

- Duplicate Extension

- Special Thread (.NET CLR)

- Hidden Parameter

- FPU Exception

- Module Variable

- System Object

- Value References

- Debugger Bug

- Empty Stack Trace

- Problem Module

- Disconnected Network Adapter

- Network Packet Buildup

- Unrecognizable Symbolic Information

- Translated Exception

- Regular Data

- Late Crash Dump

- Blocked DPC

- Coincidental Error Code

- Punctuated Memory Leak

- No Current Thread

- Value Adding Process

- Activity Resonance

- Stored Exception

- Spike Interval

- Stack Trace Change

- Unloaded Module

- Deviant Module

- Paratext

- Incomplete Session

- Error Reporting Fault

- First Fault Stack Trace

- Frozen Process

- Disk Packet Buildup

- Hidden Process

- Active Thread (Mac OS X)

- Active Thread (Windows)

- Critical Stack Trace

- Handle Leak

- Module Collection

- Module Collection (predicate)

- Deviant Token

- Step Dumps

- Broken Link

- Debugger Omission

- Glued Stack Trace

- Reduced Symbolic Information

- Injected Symbols

- Distributed Wait Chain

- One-Thread Process

- Module Product Process

- Crash Signature Invariant

- Small Value

- Shared Structure

- Thread Cluster

- False Effective Address

- Screwbolt Wait Chain

- Design Value

- Hidden IRP

- Tampered Dump

- Memory Fluctuation (process heap)

- Last Object

- Rough Stack Trace (unmanaged space)

- Rough Stack Trace (managed space)

- Past Stack Trace

- Ghost Thread

- Dry Weight

- Exception Module

- Reference Leak

- Origin Module

- Hidden Call

- Corrupt Structure

- Software Exception

- Crashed Process

- Variable Subtrace

- User Space Evidence

- Internal Stack Trace

- Distributed Exception (managed code)

- Thread Poset

- Stack Trace Surface

- Hidden Stack Trace

- Evental Dumps

- Clone Dump

- Parameter Flow

- Critical Region

- Diachronic Module

- Constant Subtrace

- Not My Thread

- Window Hint

- Place Trace

- Stack Trace Signature

- Relative Memory Leak

- Quotient Stack Trace

- Module Stack Trace

- Foreign Module Frame

- Unified Stack Trace

- Mirror Dump Set

- Memory Fibration

- Aggregated Frames

- Frame Regularity

- Stack Trace Motif

- System Call

- Stack Trace Race

- Hyperdump

- Disassembly Ambiguity

- Exception Reporting Thread

- Active Space

- Subsystem Modules

- Region Profile

- Region Clusters

- Source Stack Trace

- Hidden Stack

- Interrupt Stack

- False Memory

- Frame Trace

- Pointer Cone

- Context Pointer

- Pointer Class

- False Frame

- Procedure Call Chain

- C++ Object

- COM Exception

- Structure Sheaf

- Saved Exception Context (.NET)

- Shared Thread

- Spiking Interrupts

- Structure Field Collection

- Black Box

- Rough Stack Trace Collection (unmanaged space)

- COM Object

- Shared Page

- Exception Collection

- Dereference Nearpoint

- Address Representations

- Near Exception

- Shadow Stack Trace

- Past Process

- Foreign Stack

- Annotated Stack Trace

- Disassembly Summary

- Region Summary

- Analysis Summary

- Region Spectrum

- Normalized Region

- Function Pointer

- Interrupt Stack Collection

- DPC Stack Collection

- Dump Context

- False Local Address

- Encoded Pointer

- Latent Structure

- ISA-Specific Code

Causal Sets and Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics

Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics begins with a simple observation: execution does not unfold linearly, and logs do not represent time. What engineers habitually call timelines are conveniences imposed by representation, not properties of execution itself. Causal set theory reaches the same conclusion from a foundational perspective. It discards spacetime as a primitive and replaces it with a discrete set of events related only by possible causation. In both cases, order precedes time, and structure precedes explanation.

When software systems are examined at scale, especially under concurrency, distribution, and learning dynamics, execution reveals itself as a partially ordered world. Threads, messages, interrupts, callbacks, retries, and speculative paths do not line up neatly; they interleave, diverge, and sometimes remain incomparable. Logs and traces, therefore, record fragments of a causal order rather than a faithful temporal history. Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics treats this not as a limitation but as the starting point for reasoning.

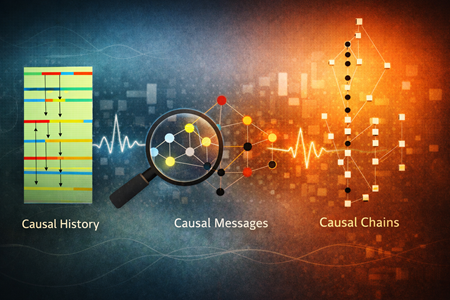

The first pattern that naturally arises in this setting is Causal History. A causal history is not a chronological log, but a directed structure extracted from trace paths and backtraces, where arrows point strictly in the direction of possible causation. Time is deliberately omitted. The absence of a time arrow is not a simplification but a discipline: it prevents the diagnostician from smuggling assumptions about simultaneity, latency, or ordering that are not justified by the data. A causal history is therefore a projection of execution into a partial order, analogous to a Hasse diagram in mathematics or a causal set in physics. It defines what could have influenced what, and nothing more.

This shift has an immediate diagnostic consequence. Many apparent anomalies disappear once logs are read as causal histories rather than timelines. Events that look “out of order” are often merely incomparable. Delays that appear pathological may be causally irrelevant. Conversely, subtle but decisive causal dependencies may be hidden among vast volumes of temporally adjacent but unrelated messages. Causal History, as a pattern, formalises this perspective and provides the foundational space for further reasoning.

Within a causal history, the diagnostician can identify Causal Messages. Not every log entry participates meaningfully in causation. Many messages are correlational artefacts, emitted because something happened nearby in time or space, not because they influenced anything. Causal Messages are those log or trace events that lie on causally relevant paths within the history. They need not be the first or last events, nor the most severe or visible ones. Their defining property is participation in a causal relation that matters for the behaviour under investigation.

This distinction is crucial in practice. Defect Groups, error clusters, or alert storms often overlap poorly with causal messages. A highly visible error may be causally downstream of an unremarkable configuration read or cache miss. Conversely, a noisy warning may be causally irrelevant. The Causal Messages pattern disciplines the diagnostician to separate causal relevance from correlation, resisting the temptation to treat frequency, severity, or proximity as proxies for influence.

Once causal messages are identified, their relationships can be further abstracted into Causal Chains. A causal chain is not a sequence in time but a composable relation between events, where the endpoint of one causal relation serves as the starting point of another. Borrowing the language of algebraic topology, causal histories give rise to zero-chains, causal messages induce one-chains, and higher abstractions emerge as chains of chains. This hierarchy mirrors constructions in discrete causal theory and algebraic topology, but it arises here from practical diagnostic needs.

Causal Chains allow diagnosticians to reason at multiple levels of abstraction simultaneously. At one level, individual events and messages remain visible. At another level, extended chains capture higher-order behaviours such as request lifecycles, failure propagation, or learning feedback loops. Two failures that appear unrelated at the level of raw logs may share a common causal chain when appropriately abstracted. Conversely, similar-looking incidents may decompose into fundamentally different chains once causality is respected.

This chaining process also explains why diagnostic insight often improves when representation becomes more abstract rather than more detailed. By collapsing low-level identities into relations, causal chains preserve structural meaning while reducing noise.

Taken together, Causal History, Causal Messages, and Causal Chains form a coherent pattern family for diagnostic analysis. Causal History defines the diagnostic spacetime as a partial order without a time dimension. Causal Messages identify the causally significant elements within that space. Causal Chains provide the mechanism for abstraction, composition, and higher-order reasoning. None of these patterns presupposes a particular technology, tooling stack, or domain. They apply equally to kernel traces, distributed systems, observability pipelines, and AI agent executions.

This framework also clarifies the role of analysis patterns. Every observability tool implements a mapping from execution into representation. Some mappings preserve causal relations faithfully, others collapse or distort them. Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics insists that these mappings themselves must be diagnosed. A broken causal chain is often not a system failure but a representational one. Causal sets provide the theoretical vocabulary to describe this precisely, while POD supplies the operational discipline to act on it.

In AI systems, the convergence becomes unavoidable. Agent behaviour unfolds as an evolving causal set in which prompts, intermediate states, tool calls, and learned updates participate in shifting causal relations. Here, causal messages may be latent, and causal chains may be probabilistic or learned rather than explicit. Yet the same patterns apply. Diagnosis becomes the art of identifying which causal structures must have existed for an observed decision to be possible.

The deeper lesson is that diagnostics is not about reconstructing what happened in time. It is about inferring what must have been causally possible. Causal History, Causal Messages, and Causal Chains are not merely analysis techniques; they are epistemic commitments. They assert that in complex systems, truth survives not as chronology but as order.

In this sense, Pattern-Oriented Diagnostics stands as a practical counterpart to causal set theory. Where physics asks how spacetime emerges from order, diagnostics asks how understanding emerges from traces. In both cases, the answer begins the same way: forget time, respect causality, and let structure speak.

PDF: https://www.dumpanalysis.org/files/Causal-Sets-Pattern-Oriented-Diagnost...